Blog

Who Are the Mongols? Exploring Mongolia’s People, Heritage, and Traditions

The Origins of the Mongols

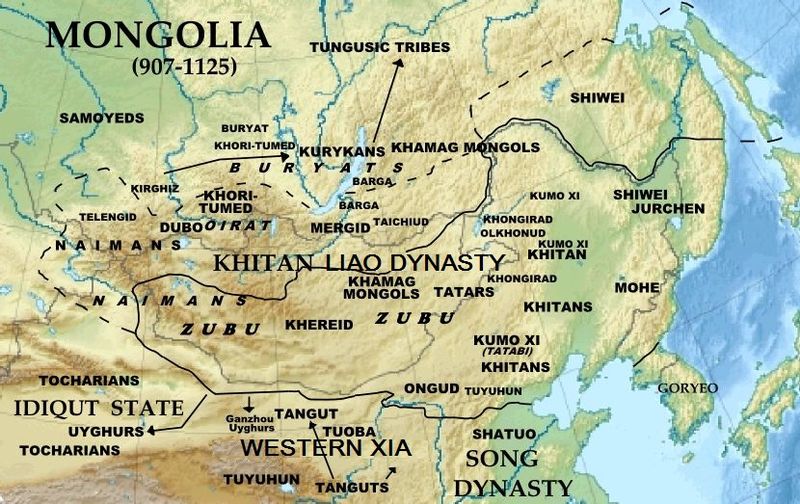

The origins of the Mongols trace back to the vast steppes of Central and Eastern Asia, where nomadic tribes roamed long before the rise of Genghis Khan. These tribes — including the Xiongnu, Xianbei, and Khitan — were the ancestors of the Mongol people, known for their mastery of horseback riding, herding, and survival in harsh climates.

By the 6th to 12th centuries, numerous clans and confederations occupied Mongolia’s grasslands, often uniting and dividing under different tribal leaders. Life centered around mobility, livestock, and a deep respect for nature — traits that became the foundation of Mongolian identity.

Turkic and Siberian People in Mongolia

Before the rise of the unified Mongol tribes, Mongolia’s vast steppe was home to a diverse mix of Turkic and Siberian peoples who played a major role in shaping the region’s cultural and genetic heritage. These groups included early nomadic confederations such as the Xiongnu, Göktürks, Uyghurs, and Kyrgyz, each leaving their mark on Mongolia’s history.

The Turkic peoples introduced early forms of statehood, writing systems, and trade connections across Central Asia. The Göktürk Khaganate (6th–8th centuries) even ruled large parts of Mongolia, establishing Orkhon as their political and spiritual center — where the famous Orkhon Inscriptions still stand today as the earliest known examples of Turkic script.

To the north and east, Siberian and Tungusic tribes such as the Evenks and Buryats shared cultural traits with the Mongols — including shamanistic beliefs, reindeer herding, and deep reverence for nature. Over centuries, intermarriage and cultural exchange between Turkic, Mongolic, and Siberian peoples shaped the ethnic mosaic that defines Mongolia today.

Mongolic Tribes Before Mongolian Empire

Before Genghis Khan unified the steppe, Mongolia was home to many independent Mongolic tribes and clans, each with its own leaders, alliances, and rivalries. These tribes shared a common language and nomadic way of life but were often divided by constant warfare and competition for grazing lands.

Among the most prominent early Mongolic groups were the Khamag Mongol, Kereit, Tatar, Merkid, Naiman, and Oirat tribes. Each played a crucial role in the political landscape of the 11th and 12th centuries. The Khamag Mongol Confederation, in particular, is considered the direct predecessor of the later Mongol Empire — and it was within this alliance that Temüjin (Genghis Khan) rose to power.

The Kereit were influential and among the first to adopt Nestorian Christianity, while the Naiman and Merkid were strong and well-organized rival tribes. The Tatars, long-time adversaries of the Mongols, often allied with the Jin Dynasty of northern China. The Oirats, ancestors of modern-day western Mongols, maintained their independence in the Altai region.

Despite their differences, these tribes shared deep-rooted traditions — a nomadic economy based on herding, complex kinship networks, and a warrior ethos that valued courage and loyalty. Their conflicts, alliances, and migrations set the stage for the unification of the Mongolic peoples under Genghis Khan in the early 13th century, giving rise to one of the most powerful empires in history.

The Mongolian Empire

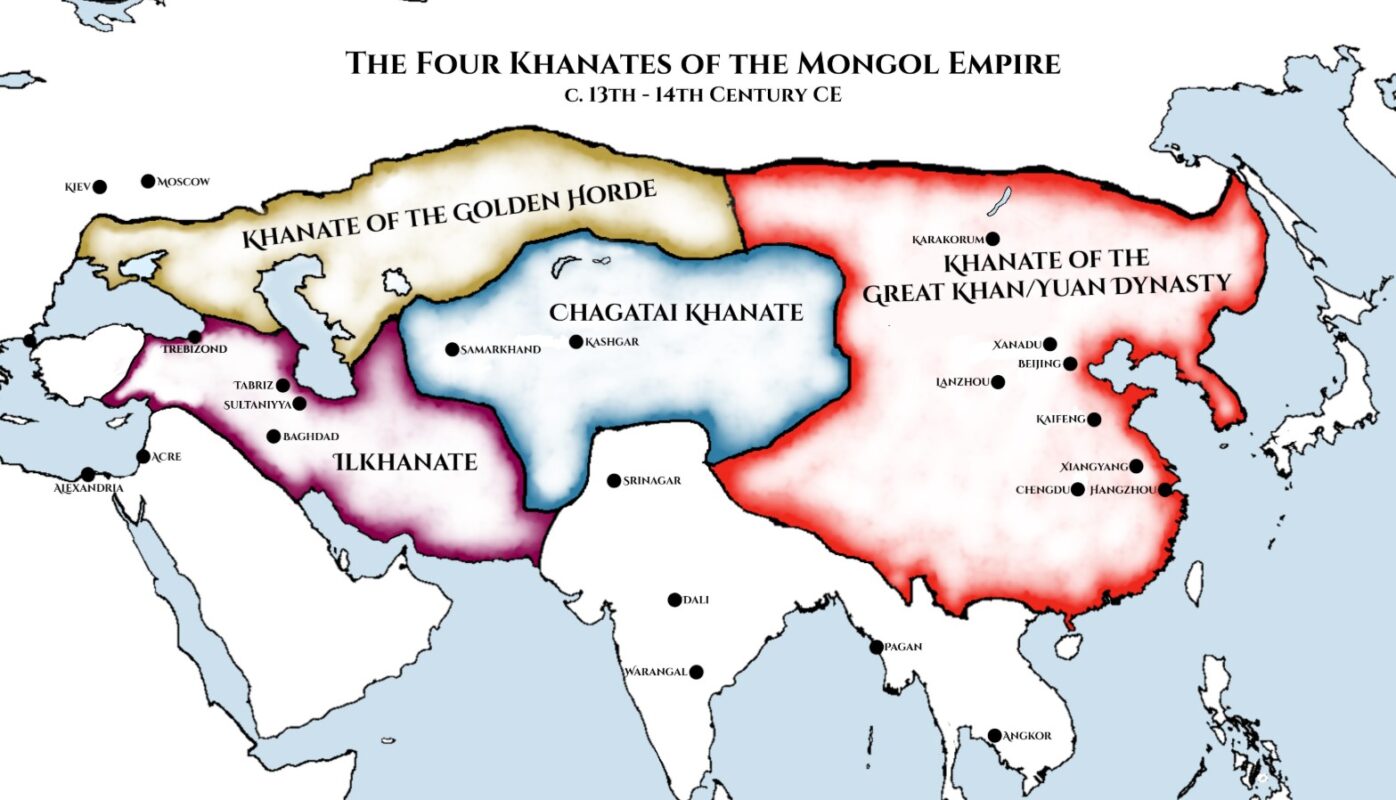

The Mongolian Empire, founded by Genghis Khan in 1206, was the largest contiguous land empire in world history. Emerging from the unification of the Mongolic and Turkic tribes of the Central Asian steppe, it expanded rapidly through superior military strategy, adaptability, and an unyielding spirit of conquest.

Under Genghis Khan’s leadership, the Mongols created a disciplined and mobile army known for its speed, coordination, and psychological warfare. They defeated powerful neighboring states such as the Western Xia, Jin Dynasty, Khwarazmian Empire, and later influenced the Islamic Caliphates and European kingdoms. By the mid-13th century, the empire stretched from Korea to Eastern Europe, encompassing vast parts of China, Russia, Central Asia, Persia, and the Middle East.

After Genghis Khan’s death in 1227, his descendants continued to expand and govern the empire, dividing it into four major khanates — the Yuan Dynasty in China, the Ilkhanate in Persia, the Chagatai Khanate in Central Asia, and the Golden Horde in Russia. Despite internal divisions, these realms maintained trade, communication, and diplomacy through the Pax Mongolica, a period of stability that revitalized the Silk Road and facilitated cultural and technological exchange between East and West.

The Mongolian Empire’s legacy endures not only in its territorial conquests but also in its contributions to global trade, governance, and communication. It laid the groundwork for modern international systems of commerce and diplomacy, while the name “Mongol” became synonymous with both awe and power across continents.

Post Mongolian Empire

After the fragmentation of the Mongolian Empire in the late 13th and 14th centuries, the once-unified Mongol world splintered into several independent khanates and regional powers. Internal rivalries, succession conflicts, and cultural assimilation gradually weakened the empire’s cohesion. The Yuan Dynasty in China, ruled by Kublai Khan, fell to the Ming Dynasty in 1368, forcing the Mongols to retreat to their homeland on the steppe.

In the centuries that followed, Mongolia entered a period of political decentralization and tribal division. Competing clans and regional leaders fought for dominance, while outside influences—particularly from China and Russia—began to shape the region’s future. The Northern Yuan Dynasty continued to rule parts of Mongolia, preserving Genghisid traditions, but lacked the strength and unity of earlier times.

By the 17th century, the Manchu-led Qing Dynasty expanded northward, bringing Mongolia under Chinese control. This period marked significant changes in Mongolian society, including the introduction of Tibetan Buddhism as a unifying religion and the decline of the nomadic military power that had once dominated Eurasia.

Despite foreign rule, Mongolian identity endured through its language, religion, and nomadic culture. The 20th century brought a new wave of transformation — with Mongolia declaring independence in 1911, followed by decades of Soviet influence and eventual democratization in 1990.

Mongolian People During Socialism

After centuries under Qing rule, Mongolia declared independence in 1911, but true sovereignty came only after the Mongolian People’s Revolution of 1921, backed by the Soviet Union. By 1924, the country became the Mongolian People’s Republic (MPR) — the world’s second socialist state after the USSR. This era transformed Mongolian society politically, economically, and culturally.

The socialist government sought to modernize Mongolia rapidly, replacing nomadic traditions with collective farming, centralized planning, and industrial development. Nomads were encouraged — and often forced — to settle, and herding became organized into cooperatives. Education, literacy, and healthcare improved dramatically, with Soviet-style schools replacing monasteries as centers of learning.

Religion, particularly Tibetan Buddhism, was heavily suppressed. Thousands of monasteries were destroyed, and many monks were imprisoned or executed during the 1930s purges. The government promoted atheism and loyalty to socialist ideals, while art, media, and education served as tools for state propaganda.

Despite the harsh control, socialism also brought progress. Urbanization increased, Ulaanbaatar grew into a modern capital, and gender equality advanced, giving Mongolian women greater access to education and employment. However, the population remained closely tied to Soviet influence — politically dependent and economically reliant on Moscow’s support.

By the late 1980s, as the Soviet Union weakened, Mongolians began demanding reform. This culminated in the 1990 Democratic Revolution, which peacefully ended 70 years of one-party rule and paved the way for a new, democratic Mongolia.

Modern Day Mongolians

Modern-day Mongolians are a people balancing ancient nomadic traditions with rapid modernization. Since the peaceful democratic revolution of 1990, Mongolia has transformed into a vibrant parliamentary democracy and market economy — yet the spirit of the steppe still defines its national identity.

Today, about half of Mongolia’s population lives in Ulaanbaatar, the capital city, which has become a bustling hub of commerce, culture, and modern life. High-rises, cafes, and digital startups coexist alongside gers (yurts) on the city’s outskirts, where rural migrants maintain a semi-nomadic lifestyle. Outside the capital, herders continue to move with their livestock across vast grasslands, preserving centuries-old customs of mobility and resilience.

Modern Mongolians take pride in their deep historical roots, from Genghis Khan’s legacy to the enduring values of hospitality, courage, and freedom. The younger generation, increasingly educated and tech-savvy, is shaping a new identity — one that honors tradition while embracing globalization, sustainability, and digital innovation.

Despite challenges such as urban pollution, rural poverty, and economic dependence on mining, Mongolians remain remarkably adaptable. Whether in the city or on the steppe, they embody the enduring harmony between heritage and progress, continuing to define what it means to be Mongolian in the 21st century.

The Mongols Beyond Mongolia

The legacy of the Mongols extends far beyond the borders of modern-day Mongolia. After the collapse of the Mongolian Empire, many Mongol groups settled across Central Asia, Russia, China, and the Middle East, leaving lasting cultural, linguistic, and genetic influences in these regions.

In China, the descendants of Kublai Khan’s Yuan Dynasty became integrated into Chinese society, yet Mongolian culture persisted in Inner Mongolia, which remains an autonomous region today. Here, millions of ethnic Mongols continue to speak the Mongolian language, practice traditional herding, and celebrate festivals like Naadam and Tsagaan Sar.

In Russia, Mongolic-speaking peoples such as the Buryats, Kalmyks, and Tuvans maintain unique blends of Mongol, Siberian, and Russian traditions. The Kalmyks, for example, are the only traditionally Buddhist group in Europe, living mainly along the lower Volga River.

The Mongol legacy also echoes in Central Asia and the Middle East, where descendants of the Golden Horde and Ilkhanate intermarried with local populations, Hazaras.

Today, the global Mongol diaspora connects through cultural organizations, festivals, and online communities that promote language, history, and identity. Whether in Inner Mongolia, Buryatia, or the Kalmyk steppe, these communities share a deep pride in their common ancestry and the enduring impact of the Mongol civilization on world history.

Diaspora of Mongolians

The Mongolian diaspora — though relatively small compared to other nations — has grown significantly since the 1990s, as more Mongolians seek education, work, and better opportunities overseas. Today, it’s estimated that over 200,000 Mongolians live abroad, forming vibrant communities across South Korea, Japan, the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

South Korea hosts the largest Mongolian community outside the homeland, with tens of thousands of workers employed in manufacturing, construction, and service sectors. Many Mongolians also study in Korean universities, drawn by cultural similarities and strong economic ties between the two countries.

In Japan, Mongolians have gained visibility through both education and sports — most notably in sumo wrestling, where athletes like Hakuho and Asashoryu became national icons. The United States and Canada attract professionals, students, and families seeking long-term stability and education, while Germany, the Czech Republic, and the UK are home to growing numbers of Mongolian expatriates, often linked by shared language schools, cultural events, and Buddhist temples.

Despite living abroad, the diaspora maintains strong connections to their homeland. Many send remittances, support cultural projects, and even return to Mongolia to contribute to business and social development. Online networks, social media groups, and festivals like “Mongolians Abroad Day” help preserve their identity and language across continents.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do Mongolians still live in yurts?

Yes, many Mongolians still live in gers (yurts) — traditional round tents made of felt and wood. Even in Ulaanbaatar, thousands of families reside in ger districts, blending ancient traditions with modern life.

How do Mongolians view Genghis Khan today?

Genghis Khan is revered as a national hero and symbol of unity. His image appears on currency, monuments, and even airports, representing Mongolia’s strength, independence, and historical

Do Mongolians still practice nomadism?

Yes, about one-third of Mongolia’s population still leads a nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyle, herding livestock and moving seasonally across the steppes.